April 27, 2017

The Affordable Care Act Young Adult Provision Found to Be Associated with a Decline in Marriage

In a recently published paper in the Journal of Human Resources, SRC researcher Joelle Abramowitz found that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) young adult provision was associated with young adults being less likely to marry. Her findings suggest that prior to the provision, some individuals married in order to obtain health insurance coverage and that the provision may enable young adults to make marriage decisions without the added consideration of insurance coverage, allowing them to search longer to find spouses who are better matches and form more stable marriages.

In a recently published paper in the Journal of Human Resources, SRC researcher Joelle Abramowitz found that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) young adult provision was associated with young adults being less likely to marry. Her findings suggest that prior to the provision, some individuals married in order to obtain health insurance coverage and that the provision may enable young adults to make marriage decisions without the added consideration of insurance coverage, allowing them to search longer to find spouses who are better matches and form more stable marriages.

In 2010, the ACA young adult provision was implemented to allow those aged between 19 and 25 to be covered by their parents' private insurance plans. The provision was intended to increase insurance coverage among young adults, who previously became ineligible for coverage under their parents' plans when they turned 19 years old.

Without such a provision, the main channels to obtain private health insurance coverage for young adults were through working for an employer who provided health insurance or through obtaining coverage as a dependent on a spouse's private insurance plan. By allowing young adults to stay on their parents' plans, the ACA young adult provision facilitated an alternative source of health insurance coverage. It follows that such a provision could then affect young adults' decisions to work or marry, as they no longer had to rely on employment or a spouse to obtain health insurance coverage.

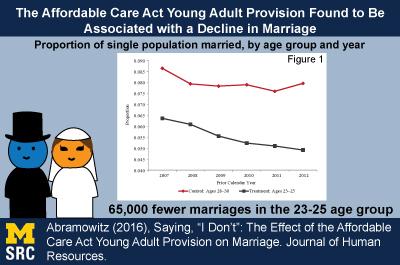

To examine whether the ACA young adult provision influenced the marriage decisions of young adults, Joelle used the 2008 through 2013 American Community Survey (ACS) and compared the marriage patterns of those aged 23-25 (who were affected by the provision; the 'treatment' group) to those aged 28-30 (who were not affected by the provision; the 'control' group). To the extent that newly eligible individuals would have otherwise married in order to obtain health insurance coverage, the implementation of the ACA young adult provision would decouple their marriage decision from health insurance coverage decision, reducing their incentive to marry.

Indeed, this was what Joelle found in her paper. Assuming that the marriage patterns of the treatment and control groups would have followed the same patterns in the absence of the ACA young adult provision, the difference between the two groups net of the time trend (which, in statistics jargon, is the 'difference-in-differences estimate') can be interpreted as the effect of the young adult provision on the likelihood of marrying. Among those aged 23-25 who were not married in the year prior to the ACS survey, the likelihood of marrying during the survey year fell, representing approximately 65,000 fewer people in that age group marrying each year.

While this analysis did find that those aged 23-25 were less likely to marry, it does not necessarily suggest that individuals are less likely to eventually marry. Rather, the provision may only result in young adults delaying marriage either in order to search longer for a spouse who is a better match or to put off the marriage decision until they age out of their parent's coverage at age 26. Distinguishing 'marriage delayed' versus 'marriage foregone' would require subsequent years of data allowing the researcher to follow the treated group into older ages and examine their marriage decisions.